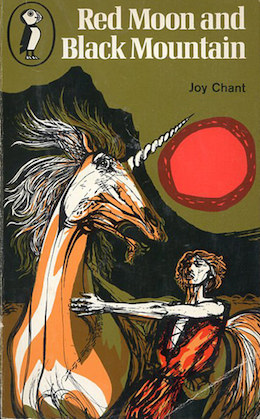

Of all the books that shaped my youth as a writer, Red Moon and Black Mountain has to be in the top five. The prose, the characters, the plotting—they sank into my bones. And they’re still there, many years later.

A lot of years. When I pulled the book off the shelf and checked the copyright page, I was startled to see “First Printing.” Omigod, dare I even crack this precious and much-read volume? But there was a deadline, and there is no ebook, and hard copies are not terribly difficult to find but they take a while to travel to my hinterland. So I read with care, and I read, this time, for the horses.

As with Mary Stewart’s Airs Above the Ground, I remembered a lot more horse-stuff than was actually there. We all focus on what matters to us. And really, when a book is mostly about a boy from our world who is taken to another and set among a tribe of horse people, that focus is pretty much inevitable.

I would have said that, like Stewart, Chant is not a horse person, as in, not about the horses, but I’d be wrong. According to Wikipedia, Vandarei began as Equitania, the imaginary kingdom of a horse-mad tween and early teen (actually two—her fellow-creator has been consistently elided from the narrative, except in the Acknowledgement of the book itself, which names Ann Walland with thanks for “her half of Khendiol”). But she does seem to have outgrown the passion, as many girls do. “They discover boys,” we say, “and that’s it for the horses.” (Though maybe later, after their daughters grow up and out of it in their turn, they may find the horses again.)

What we have here is true high fantasy, with a strong debt to Tolkien and Narnia and other, lesser-known fantasists, but in combinations and with overtones and undertones that are all its own. Just for starters, the world is not all lily-white except for the swarthy villains. The Khentors are Mongols with a dash of Plains Indian, and the Humarash are explicitly Black and from very far away—which for the work of a British author in 1970 (and written, we can presume, in the Sixties) is remarkable. The villains are mostly white and blond when they’re not trolls or other nonhumans, and the Big Bad is basically a Black Numenorean (that being a reference to his sorcery rather than his skin color).

As for the horses, they’re everywhere in this preindustrial world. Horses draw the chariots of the vastly tall, pale-skinned, black-haired and grey-eyed Harani, ponies carry everyone from Khentor children to the terrible earth-goddess Vir’Vachal, and the very horselike unicorns called davlenei (or simply horses) are the mounts of the (always male) Khentor warriors.

The davlenei—singular re-davel—are described with great love, particularly the immortal Dur’chai. Like Oliver-who-becomes-Li’vanh, he is sent to the world of Vandarei by the gods, and his purpose is to help Oliver defeat the evil Fendarl. Oliver’s much younger brother and sister, Nicholas and Penelope, are also sent, but to a different part of the world, and Penelope is mostly about wearing a lot of petticoats and being the doom of Bannoth thanks to her blue-blue eyes (blue being the color of death here), while Nicholas gets to travel all over the place and make friends with a magical boat called Dancer.

Oliver lives a whole life on the Northern Plains among a tribe of Khentors called the Hurnei. He grows to manhood, learns to be a warrior, and rides Dur’chai, the Endurer. Dur’chai is splendid, of course: the color of old bronze, with golden mane and tail, and a spectacular horn. When we first meet him, we get a sense that he has more than simple equine intelligence.

The horse turned to keep watching him and Oliver caught a glimpse of his eyes. A thrill of wonder tingled through him. For they were thinking eyes: lively, intelligent. He had never seen such eyes in an animal before.

Naturally Oliver alone can approach the immortal horse, because he’s meant for Oliver. They’re both Chosen for a specific task, though it takes quite some time for Oliver to realize this.

In the meantime he treats Dur’chai more or less as a normal horse. Rides him, trains on him, travels around with him. Once we know Dur’chai is something else, we don’t get to see it again until the end. Mostly he’s transportation, and bragging rights. Oliver doesn’t connect to him the way he does to some of the humans around him. He’s a tool, like the sword of Emneron and the Shield of Adamant, though with somewhat more ability to act for himself.

When I first read this book, and reread it I forget how many times, I didn’t mind. I was so caught up in the epic sweep, the beautiful language, the sheer force of story, that the lack of genuine personality in any of the horses, even the most epic of them all, slid right past me. I had too many other priorities.

Rereading it this time, I missed what might have been there. The bond between the horse and his chosen rider. The poignant realization that it will, must, end, and the horse will return to his immortal fields and the rider to his ordinary Earth. The sorrow of parting—which is not there at all. Oliver just leaves him and that’s that. It’s all about Oliver and what he wants and what he chooses to do. Dur’chai is not included in his calculations.

As for the davlenei in general, I have questions. Some may have been answered in the few other works set in this world, but they’re left open here. It’s clear the boys who aspire to be men go away in the spring and find their re-davel, which means there are wild herds to capture them from. But at the same time, there’s a King stallion living with the tribe, who determines when the tribe leaves a camp and where it will go, which is not really accurate—with horses, it’s the senior mare who makes those decisions. I suppose she might do that and then get the stallion to make all the noise and get everybody moving, since noise is what stallions are mostly about.

And that’s another question. Are there female davlenei? Do boys capture both genders or only stallions? If they only capture stallions, where are the mares? Because if the tribe is breeding them, they won’t need to send people out to capture wild ones. Unless the herds are all ponies and normal horses, and the davlenei are unique and keep to themselves? And don’t interbreed with regular horses?

Not that any of that matters to this story. I just start thinking, and my mind gallops off on tangents.

I do wish Oliver had had more of a real relationship with Dur’chai. Just a little. And that it had been more of a mutual thing when they came to the last battle, and then to what happened after. More interaction. More feeling for each other.

Makes me wonder if horsekids who stay with horses have this, and horsekids who discover boys don’t. Or lose it as they mature, the way children in mid-century fantasies lose magic.

It’s almost as if this book and key aspects of its worldbuilding are about this: about what happens to girls when they hit puberty and shift their focus from animal companions to human mates. Because one of the biggest problems with this world is what it does to female sexuality.

A woman in Vandarei can be a Star Enchantress if she has the right genetics, but if she falls in love with anyone but a fellow Enchanter, she loses all her powers and her star dies. That happens to Princess In’serinna when she marries the part-Khentor, part-Harani prince Vanh, and she dwindles into a wife. A princess wife, but a wife.

A woman among the Khentors loses even more. When she becomes a woman, she gives up everything. Riding, hunting, fighting. She wraps herself in a long robe and confines herself to her wagon. Which is necessary, we’re told, because “to a nomadic people on the move the women were no more than baggage, completely dependent on the men.” Sitting targets. Incapable of defending themselves in any way.

Bitch. Please.

I understand that many cultures of our world do this to women, and few or no cultures fail in some way to diminish a woman when she reaches childbearing age. It’s called patriarchy and it’s damned persistent. There’s also an ongoing and frequently acrimonious debate about secondary-world fantasy and how much, if at all, it should mirror the cultures and mores of our world.

Nevertheless, even by the standards of “it’s medieval so women have to be completely oppressed,” Chant’s world is extreme. It’s very Sixties in its way, with a similar undertone to Airs Above the Ground, whose protagonist has mostly given up her veterinary practice to marry and will give it up completely when the babies start coming, and she accepts this. A girl’s life contracts when she hits puberty, contracts further when she marries. It’s the way of the world. Women are “utterly helpless.” Men do the fighting and the rescuing.

But there’s more to this, and a level of subversion even while it’s overtly accepted. Khentor women may lose their freedom in the sense that men know it, but they gain something else. They become devotees of the earth goddess, the Great Mother. And her rite is the rite of blood.

The end of the novel, like Tolkien’s great work, goes on past the climactic victory to something deeper and, in this case, darker. Nicholas and Penelope return home in a divine chariot, all very pretty and expected. But Oliver, who made himself far more a part of this world, isn’t given the easy way out. He has to make his own way. And that way is terrifying.

It’s called the royal sacrifice. It’s the voluntary choice to save the world by dying for it. (Hear the symbols clashing.) He has to do it because all the high epic drama and the battles and the magic have awakened something neither good nor evil, but so ancient and so inimical to humans that it can’t be allowed to continue. It’s the Earth itself, in the form of Vir’Vachal on her pony.

She did not so much ride the pony as let it bear her, and she turned to one side, one hand resting on its quarters, looking about her. Her eyes passed over the travellers, and Nicholas shuddered. He could not see their colour, but he felt their fierceness. A slow, deep savagery moved in them, and as she rode heat rippled from her. Not warmth—heat.

This is pure, raw, unmitigated female sexuality, and it’s terrifying—and not just to a ten-year-old English boy. It’s the darkest archetype of the horsegirl, like Thelwell gone mad. And it has to be put down hard.

By, inevitably, the young man just past his own puberty. Making the ultimate sacrifice. Destroying himself to suppress her. He was strong, strong as she herself—and he would bind her. Willingly, consciously—and in so doing, finally finding his way home.

It’s not an accident that Vir’Vachal rides a pony. Ponies are a girl’s freedom. Binding her means taking her away from the pony and locking her up in a wagon and rendering her helpless. While the man graduates from the pony to the unicorn (twisting the myth of the creature who can best and only be controlled by the female virgin), the woman descends from the pony to darkness and physical constraint.

Buy the Book

The Ruin of Kings

At the same time, once she surrenders her freedom, she becomes the unspoken ruler of the tribe. Like the girl Mneri she becomes its Luck and its priestess. And when the Goddess demands her due, it’s the women who perform the sacrifice, the young men who are chosen to be sacrificed.

Men may ride and hunt and fight, but women ultimately control them. That’s the dark secret of patriarchy, the story that’s told to keep women in their place but believing themselves secretly powerful, as women in the Sixties well knew.

It’s horrifying now, especially to younger women. It makes this book very hard to reread, because it cuts so ferociously against the kind of world that we want to see. Oh, you can be an Enchantress and marry an Enchanter, but you give up all human warmth and you had better not fall in love with an ordinary human. Aside from the fact that you have to be an elite of the elite and physically perfect, which is a whole other degree of problematical.

Even the retro view of nomadic culture—hello, secondary world. Women can ride, hunt, fight. They’re in no away defenseless. Wagons hold them down? What about houses? Castles? Cities? It does not make logical sense.

What it does is tell us something about the culture from which its author came, and the ways in which women and girls were made to keep their places. Horses are very much a part of that: who can have them, and what kind of horse that person can have, and what that horse means within the context.

As for Dur’chai…I’ve had my own ways of processing that, through the years and the books and the stories and the articles. He has a lot of offspring, one way and another.

Next time I’m moving on to another great portal fantasy with horses, C.J. Cherryh’s Gate of Ivrel. That’s a completely different take on the genre, and the horses are very cool. Also, considering the life they have to live, extremely chill.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent short novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.